2

Background

The use of models

2.1

Firms’ use of models[4] covers a wide range of areas relevant to its business decision making, risk management, and reporting. Business decisions should be understood here as all decisions made in relation to the general business and operational banking activities, strategic decisions, financial, risk, capital, and liquidity measurement and reporting, and any other decisions relevant to the safety and soundness of firms. Firms' increasing reliance on models and scenario analysis to assess future risks and the evolution of sophisticated modelling techniques highlights the need for sound model governance and effective MRM practices. Inadequate or flawed design and implementation, and inappropriate use of models could lead to adverse consequences.

Footnotes

- 4. Model use is defined here as using a model’s output as a basis for informing business decisions.

- 17/05/2024

Quantitative methods and models

2.2

A wide variety of quantitative calculation methods, systems, approaches, end-user computing (EUCs) applications and calculators (hereinafter collectively ‘quantitative methods’) are often used in firms’ daily operations, ie output supports decisions made in relation to the general business activities, strategic decisions, pricing, financial, risk, capital and liquidity management or reports, and other operational banking activities. Good risk management practices involve quantitative methods that support business decisions being tested for correct implementation and use.

- 17/05/2024

2.3

Models are a subset of quantitative methods. The output of models are estimates, forecasts, predictions, or projections, which themselves could be the input data or parameters of other quantitative methods or models. Model outputs are inherently uncertain, because they are imperfect representations of real-world phenomena, are simplifications of complex real-world systems and processes (often intentionally), and based on a limited set of observations. In addition to testing for correct implementation, for models, good risk management practices involve:

- i. the applicability to the decisions they support being verified; and

- ii. the validity of the underlying model assumptions in the business context of the decisions being assessed.

- 17/05/2024

2.4

For the purposes of the expectations contained within this SS, a model is defined as a quantitative method that applies statistical, economic, financial, or mathematical theories, techniques, and assumptions to process input data into output. Input data can be quantitative and/or qualitative in nature or expert judgement-based and the output can be quantitative or qualitative. A working definition of a model is important as it brings consistency and clarity for firms implementing MRM frameworks.

- 17/05/2024

2.5

However, advances in technology and data processing power increasingly enable deterministic quantitative methods such as decision-based rules or algorithms to become vastly more complex and statistically orientated, conditions that would typically entail challenge to their applicability in supporting important business decisions. Understanding the potential impact the use of models and complex quantitative methods could have on firms’ business and safety and soundness is therefore equally important.

- 17/05/2024

Model risk

2.6

Model risk is the potential for adverse consequences from model errors or the inappropriate use of modelled outputs to inform business decisions. These adverse consequences could lead to a deterioration in the prudential position, non-compliance with applicable laws and/or regulations, or damage to a firm’s reputation. Model risk can also lead to financial loss, as well as qualitative limitations such as the imposition of restrictions on business activities.

- 17/05/2024

2.7

Models’ outputs may be affected by the choice and suitability of the methodology, the quality and relevance of the data inputs, and the integrity of implementation and ongoing scope of applicability of a model. The continued suitability of the model may also be impacted by changes to the validity of any assumptions supporting the model’s use case (eg the macroeconomic assumptions encoded in the model, or assumptions about the continued relationship between variables in historical data) or inappropriate use.

- 17/05/2024

2.8

Individual model risk increases with model complexity. For example, the PRA would expect higher model risk for more complex models that are difficult to understand or explain in non-technical terms, or for which it is difficult to anticipate the model output given the input. Similarly, higher uncertainty in relation to inputs and construct, eg complex data structures, low quality or unstructured data would increase model risk, including models where the results and findings cannot be easily repeated or reproduced. Overall (aggregate) model risk increases with larger numbers of inter-related models and interconnected data structures and data sources.

- 17/05/2024

Model risk management and the model lifecycle

2.9

Model risk can be reduced or mitigated, but not entirely eliminated, through an effective MRM framework. Effective MRM starts with a comprehensive governance and oversight framework supported by effective model lifecycle management.

- 17/05/2024

2.10

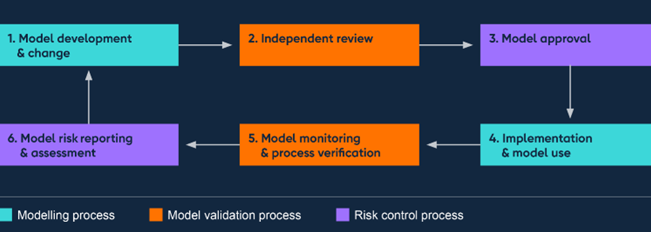

The model lifecycle can be thought of as being made up of three main processes:

- i. the core modelling process – model development, implementation, and use;

- ii. model validation – the set of activities intended to verify that models perform as expected, through:

- a) a review of the suitability and conceptual soundness of the model (independent review);

- b) verification of the integrity of implementation (process verification);

- c) ongoing testing to confirm that the model continues to perform as intended (model performance monitoring); and

- iii. model risk controls – the processes and procedures other than model validation activities to help manage, control or mitigate model risk.

- 17/05/2024

2.11

The sequence of modelling-validation-control activities describes the various stages in a model’s lifecycle.

- 17/05/2024

Diagram: the model lifecycle

- 17/05/2024

Organisational structures, validation, and control functions

2.12

Establishing the roles and responsibilities for the three main model lifecycle processes is firm-specific and depends on a firm's business model and structure of business lines. The primary roles are usually defined as follows:

- i. The model owner is the individual accountable for a model's development, implementation and use, and ensures that a model's performance is within expectation. The model owner could also be the model developer or user.

- ii. The model user(s) is the individual(s) that relies on the model's outputs as a basis for making business decisions. Model users typically identify an economic or business rationale for developing a new model and/or the need to change or modify an existing model, and may be involved in the early stages of model development and ongoing monitoring activities.

- iii. Model developer(s) is/are the team or individual(s) responsible for designing, developing, evaluating (testing), and documenting models.

- 17/05/2024

2.13

Large firms often establish a designated model risk function (MRM function) within their risk management or compliance departments. The MRM function may be separate from the model validation function, in which case they have distinct responsibilities. The MRM function is usually responsible for creating and maintaining the MRM framework and risk controls. Where firms do not establish a designated MRM function, the responsibilities for the MRM framework and risk controls are usually assigned to individuals and/or model risk committees (or a combination). Regardless of the structure of firms’ business lines, the effectiveness of MRM control functions is affected by their stature and authority, for example to restrict the use of models, recommend conditional approval, or temporarily grant exceptions to model validation or approval.

- 17/05/2024

2.14

The validation function’s primary responsibility is usually to provide an objective and unbiased opinion on the adequacy and soundness of a model for a particular use case. Validators should therefore not be part of any model development activities, nor have a stake in whether or not a model is approved. Ensuring model validators’ impartiality can be achieved in various different ways, eg having separate reporting lines and separate incentive structures from the model developers, or an independent party could review the test results to support the accuracy of the validation and thereby confirm the objectivity of the finding of the independent review.

- 17/05/2024

2.15

Regardless of the model type, risk type, or organisational structure, effective MRM practices are underpinned by strong governance and effective model lifecycle management, consisting of robust modelling, validation, and risk control processes.

- 17/05/2024